Jul 17, 2025 | User Research, UX Strategy & Planning |

In today’s fast-paced and agile teams, democratizing research—allowing designers, product managers, and even marketers to run user studies—is becoming increasingly common. It’s often seen as a way to empower teams, speed up insights, and make user research more accessible.

At Netizen eXperience, we help clients build better digital products through UX research and design. While our UX Designers have always practiced user-centered thinking, it’s our UX Researchers and Consultants who lead the structured research process—from interviews and usability tests to data analysis—to uncover deeper insights that shape smarter design decisions.

As we embrace research democratization, we’ve started equipping our UX Designers with research skills through structured training and hands-on practice. Along the way, we’ve learned that democratizing research isn’t as simple as handing someone a “research 101” guide. Behind the scenes, non-researchers often face significant challenges that are easy to overlook.

Why We Chose to Democratize Research

For us, the decision to democratize research wasn’t just about solving resource constraints or meeting tight deadlines. It was a deliberate step toward developing more well-rounded designers who don’t just create solutions but genuinely understand the people they are designing for.

By involving designers directly in user research, we wanted to help them:

- Build stronger empathy by hearing user stories firsthand

- Refine their designs based on real user feedback, not just assumptions

- Expand their skill set beyond design execution to include various user research methods

We believe that democratizing research is more than just sharing tasks—it’s about deepening the connection between design and research and nurturing design empathy by involving designers in the full research journey. This enables our team to design with even greater care, curiosity, and empathy for real users.

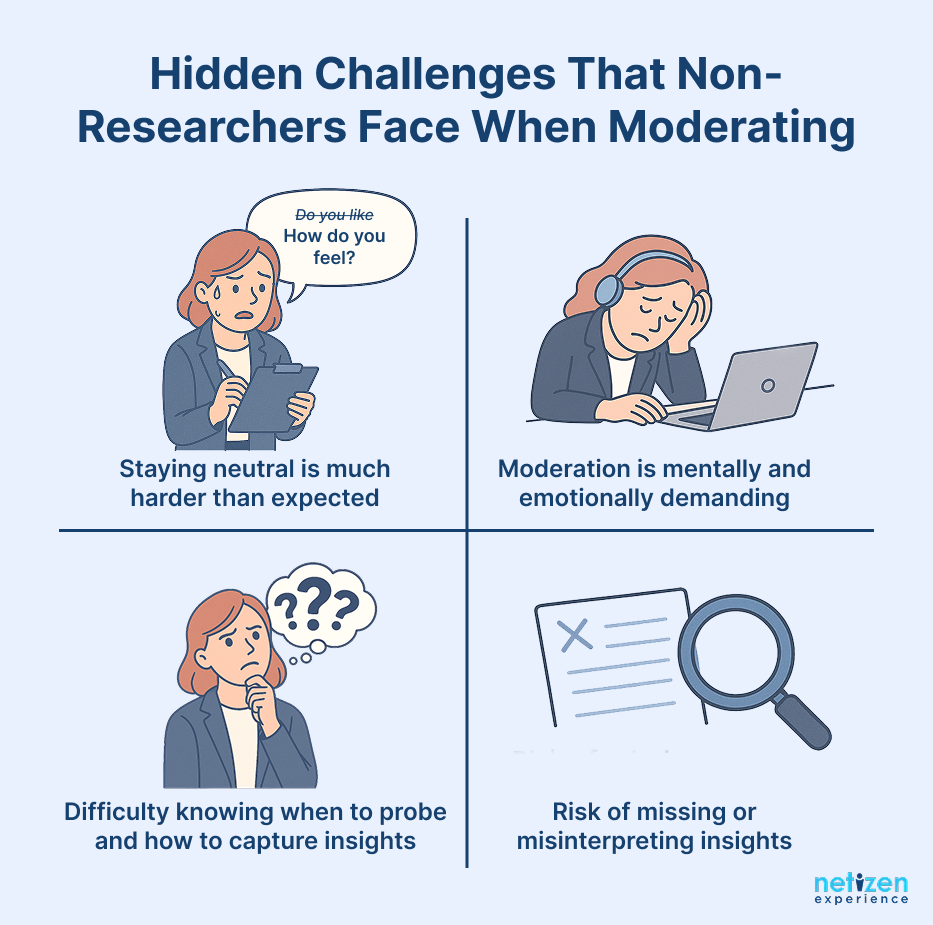

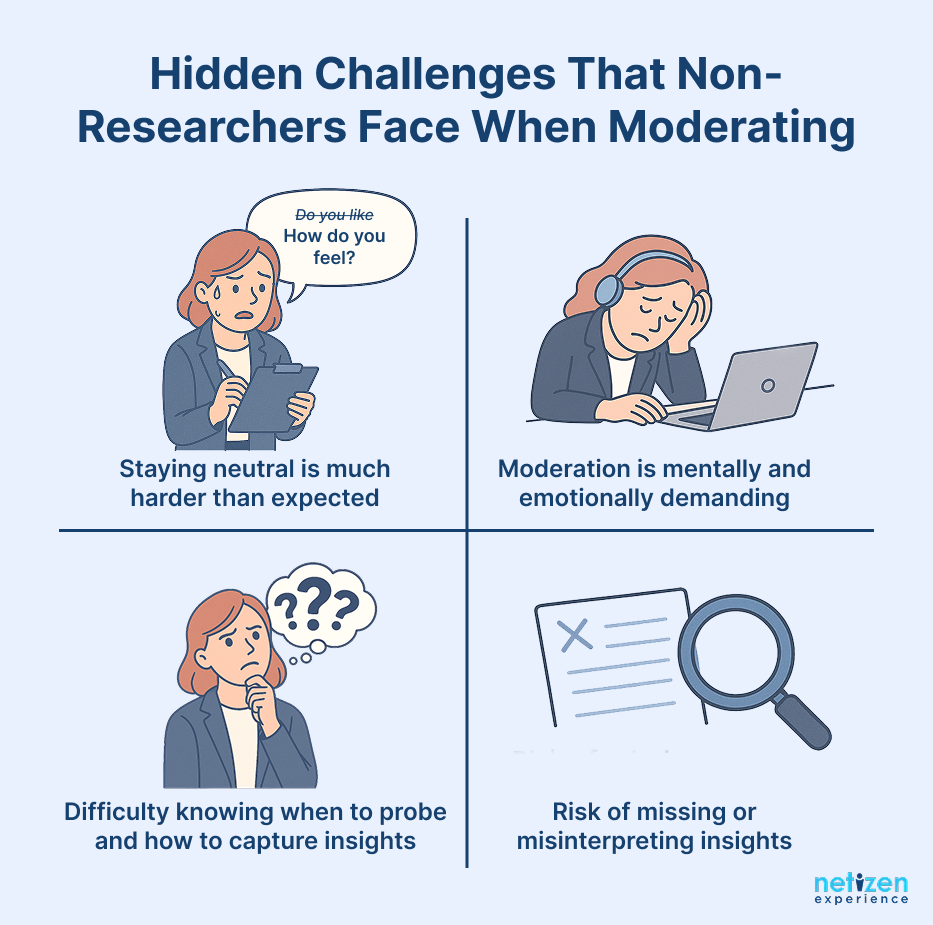

The Hidden Difficulties Non-Researchers Face

We knew stepping into research wouldn’t be all smooth sailing, but we wanted to find out what really happens when non-researchers take the lead.

To better understand the learning curve and challenges faced by non-researchers, we spoke to two of our UX Designers who were recently trained to moderate usability testing sessions and have participated in research projects. Their experiences shed light on the hidden difficulties that often come with democratizing research.

1. Staying Neutral Is Much Harder Than Expected

Designers often struggle to separate their role as design creators from their role as research moderators. As designers, it’s instinctive to start thinking about improvements the moment feedback surfaces.

Staying neutral, asking unbiased questions, and resisting the urge to validate their work require discipline, and that only comes with practice.

As one designer reflected:

“I know the answer, but I need to stay neutral. Sometimes I lead unintentionally or get stuck because I don’t know what to say.”

Even when designers understand moderation principles in theory, nervousness and inexperience can make them difficult to apply in the moment.

2. Moderation Is Mentally and Emotionally Demanding

The cognitive load of moderating is often underestimated. Moderators must:

✔️ Listen actively

✔️ Manage time

✔️ Think of follow-up questions

✔️ Navigate unexpected user responses

And they have to do this on repeat, often across five to ten sessions in a row, while maintaining the same level of focus and emotional presence each time.

One designer shared that the pressure was overwhelming, especially because it’s not something they’re used to.

“I like working with researchers because they offer a different perspective. But when I have to moderate, I’m stepping outside my comfort zone and it’s very, very stressful.”

As designers, they are comfortable answering stakeholder questions because they know their designs inside and out. In design presentations, they can prepare and control the narrative. But in moderation, the conversation is fluid, unpredictable, and requires them to stay neutral while thinking on their feet.

This kind of real-time cognitive and emotional effort can be draining for anyone, regardless of personality type, especially when it’s outside their usual day-to-day responsibilities.

3. Navigating the Grey Areas: When to Probe and How to Capture Insights

Effective research requires more than just following a script or taking notes. It demands real-time judgment; knowing when to dig deeper, when to move on, and how to make sense of what you’ve heard.

Non-researchers often second-guess themselves during moderation:

- Did I probe enough?

- Am I leading the participant?

- Was that detail important or not?

Even after the session, the uncertainty continues. Designers shared that summarizing and documenting what they heard wasn’t as straightforward as expected. They sometimes struggled with phrasing insights neutrally, avoiding overly design-focused takeaways, and identifying key behavioral patterns.

These grey areas can lead to blind spots or misinterpretations if non-researchers are left to figure it out on their own.

4. The Risk of Missing or Misinterpreting Insights

Without proper support and guidance, non-researchers may latch onto surface-level feedback or focus too narrowly on their own designs, missing deeper usability or user behavior issues.

The risk is especially high when designers moderate their own work. Familiarity with their design can create blind spots especially when designers are closely attached to the work being tested.

When designers step into the moderator’s role, they may unintentionally defend their designs or overlook critical signals, not out of ill intention, but because they’re too close to the product.

“When you test your own design, it’s really hard to stay neutral because you know it too well.”

So Why Let Designers Do User Research?

Yes, letting designers moderate user sessions introduces real challenges—staying neutral to avoid bias, cognitive strain, ambiguous probing, and the risk of misreading insights. But these challenges aren’t roadblocks, they’re investments. When designers confront these hurdles firsthand, they begin to:

- Develop ownership of outcomes: A designer who runs research, rather than just reviews reports, is more aligned with what users actually need, reducing the gap between design intent and real-world use.

- Strengthen cross-functional empathy: Direct involvement in user conversations gives product, design, and even marketing teams a deeper stake in insights, breaking down silos and leading to more cohesive decision-making.

- Scale research impact strategically: Empowering designers to handle routine studies allows senior researchers to focus on complex, high-stakes projects.

- Embed a user-centric culture: Broader participation in research makes user-centered thinking a shared norm, not a siloed function.

For decision-makers, this translates into faster iteration cycles, more grounded design decisions, and less dependency on overstretched research teams, and all without compromising user understanding.

And for the designers themselves, the value is just as transformative. Our designers found that conducting research themselves gave them a deeper, more personal connection to users, something they couldn’t fully achieve by just observing.

This fosters not only deeper design empathy, but also greater clarity in their decisions. Being present during user interviews helped them iterate more purposefully, defend their ideas more convincingly, and design with more accuracy from the start.

After all, it’s not about replacing researchers—it’s about building a more research-literate team where insights flow faster, bias is acknowledged, and design decisions are driven by real user evidence, not assumptions.

The Heart of Responsible Democratization

Democratizing research doesn’t mean everyone can (or should) run research independently. It’s about putting the right guardrails in place: clear processes, proper training, mentorship, and well-defined boundaries for when non-researchers can lead and when experienced UX researchers must step in.

At its core, it’s about mutual empathy and shared responsibility.

When done poorly, democratization risks introducing bias, missing key insights, and compromising research quality. But when teams build the right support systems, it can foster deeper empathy, improve research literacy, and encourage more thoughtful collaboration across disciplines.

When done well, democratization isn’t just a practical strategy, it becomes a cultural mindset.

A mindset that grows stronger when more people listen, more people learn, and more people genuinely care about getting it right.

Democratizing research responsibly isn’t just good practice—it’s good culture.

About the Author:

Wai Yee is a UX Researcher with four years of experience driving research initiatives in the fintech and insurance sectors, shaping digital strategies and product experiences. Outside of work, you’ll likely find her chasing hiking trails or perfecting her cup of coffee.

Jul 3, 2025 | Case Studies, Respondent Recruitment, User Experience, User Research, UX Strategy & Planning |

When designing digital solutions for underserved communities who are often overlooked, research can’t be business as usual. It has to be human-first, humble, and grounded in reality.

We partnered with Friendsuretech—a fintech innovator—on their mission to design myKawan, a financial literacy tool for Malaysia’s B40 communities. Together, we aimed to uncover the real-world challenges these communities face around money, trust, and technology so that the final product could truly serve their needs.

And while empathy drove the approach, the business case is just as compelling. Inclusive financial tools don’t just build social equity; they build market opportunity. A study of Chinese banks, for instance, found that when fintech solutions focused on underserved groups, it led to stronger lending growth and financial resilience, especially in rural areas. Reaching underserved communities isn’t a detour from profitability; it can be a driver of it.

This wasn’t just about testing a prototype. It was about building understanding from the ground up. And that meant doing research a little bit differently.

Who Are the Underserved? Giving Voice to Malaysia’s Low-Income Communities

Before we could design a meaningful research approach, we first had to be clear about who we were designing for. Conversations about inclusion often start with good intentions, but without a shared understanding of who is being left out, it’s easy to miss the mark.

In this project, the focus was on Malaysia’s B40 group: the bottom 40% of households by income. This group often faces layered, systemic barriers that go far beyond financial strain. Limited digital access, lower financial literacy, geographic isolation, and a lack of tailored financial services all contribute to their exclusion from the wider economy. As such, this research effort is specifically aimed at reaching these underserved communities often left out of digital product development.

In short, many in the B40 community are navigating life without the tools, support, or opportunities that others might take for granted. They are also frequently overlooked in traditional product development, not due to a lack of relevance, but because they’re harder to reach through conventional UX research methods.

What made this project stand out was Friendsuretech’s early commitment to going beyond assumptions in building a financial literacy tool that actually works for the underserved. It meant listening to real stories, real behaviors, and real constraints.

Together, we tailored a research approach that met communities where they are; physically, emotionally, and digitally.

This commitment aligns with a bigger picture too. Financial inclusion isn’t just a feature but a foundation for social equity. The United Nations links it to eight of its Sustainable Development Goals, and Bank Negara Malaysia has highlighted inclusive finance as key to national progress.

Together with Friendsuretech, we aimed to translate these ideals into action by starting with something simple but powerful: listening.

Breaking Barriers: Adapting Our UX Research Operations

From the beginning, we knew reaching Malaysia’s B40 community wouldn’t be as simple as sending out a few screening surveys and booking slots in our UX lab. Many of the tools and assumptions we typically rely on just didn’t apply here.

In our journey to understand the B40 group, we had to rethink every step—from outreach to participation—to truly hear their voices. Here’s how we turned the main obstacles in this journey into opportunities for meaningful research.

💡 Challenge 1: Limited Access to the Low-Income Communities

Our first hurdle became clear almost immediately: we couldn’t reach participants through any of the conventional recruitment strategies. Recruitment channels like social media and user panels just weren’t reliable enough to get the demographic we’re looking for.

These communities don’t typically show up in databases or online records, and financial vulnerability isn’t something most people openly share. Add to that a healthy skepticism toward unknown outreach, and our efforts often felt like spam—or worse, a scam. Malaysia saw nearly 3 million scam calls in 2024 alone, an increase of 82.8% from the year before. Without a strong connection, there was no reason for them to engage.

🚀 What We Did: Partnering with People They Already Trusted

So, we turned to trusted community leaders, NGOs, and local organizations that already had strong relationships with these communities. These partners became our bridge to the people we hoped to reach.

As they had already built relationships through previous support or outreach, their involvement gave our research credibility. Instead of showing up as strangers asking personal questions, we were introduced through familiar, trusted faces. That shift, from cold outreach to community-based connection, made all the difference.

💡 Challenge 2: Earning Trust and Overcoming Hesitation

With the community leaders on board, they helped spread the word about our research to those who might be a good fit. But even when people agreed to participate, financial topics brought hesitation.

For many, this was the first time they were asked to share their personal money habits and struggles with outsiders. A few even wondered if they had anything valuable to contribute at all. This reflected something deeper: a learned invisibility, a sense that their voices had rarely been heard, let alone valued, in product development.

🚀 What We Did: Slowing Down to Create Comfort, Bit by Bit

So instead of overwhelming participants with too much upfront, we took things slow. We first met with community leaders to explain the research clearly and openly. They then passed that understanding on to their communities, helping build awareness and trust in small, steady steps.

By the time participants showed up for the actual sessions, they already had a sense of what we were doing and why. This gradual introduction gave them space to warm up to the idea, and by the time we explored more personal topics, they were ready to share more openly. This approach showed them that their everyday experiences did matter and were exactly what we needed to hear.

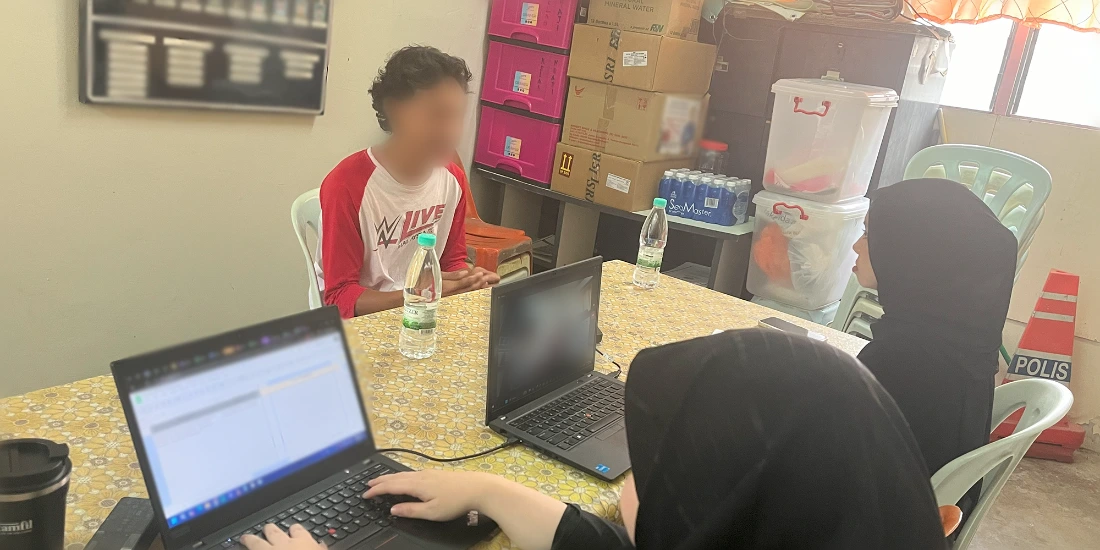

Our team with one of the community members helping drive recruitment

💡 Challenge 3: Logistical Constraints

Just as things were starting to click, we ran into another issue: logistics. Even when participants were open to joining, the logistics of showing up often became the dealbreaker. Traveling to our research facility meant navigating unfamiliar routes, figuring out transportation, dealing with parking, and then still needing to make time in a day already packed with responsibilities.

For those just getting to know us through community introductions, trust was still in its early stages. Without a strong relationship yet in place, the effort required to attend—on top of everything else—felt like too much, even for those who were genuinely interested.

We were especially eager to include two key groups who both had their own obstacles in joining our research:

- University students, juggling lectures, assignments, and part-time jobs with little breathing room.

- Housewives, whose days were fully booked with childcare, cooking, and managing the household.

🚀 What We Did: Bringing Research to Them

So instead of asking them to come to us, we went to them. We held sessions at community centers in their neighborhoods and offered flexible time slots, including weekends and evenings.

By making the process as easy and respectful as possible, we removed the pressure and made space for their voices to be heard, on their terms.

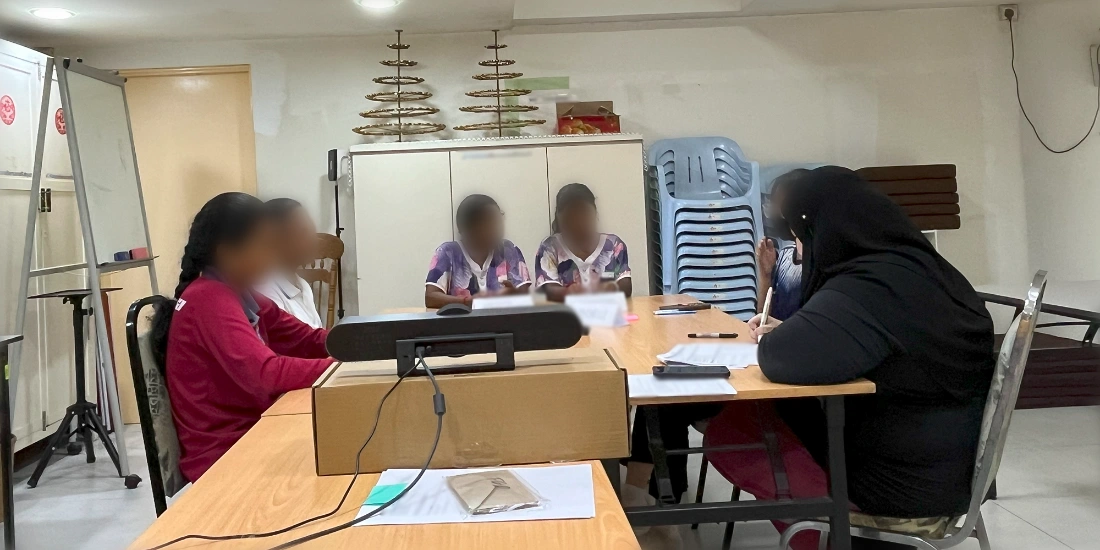

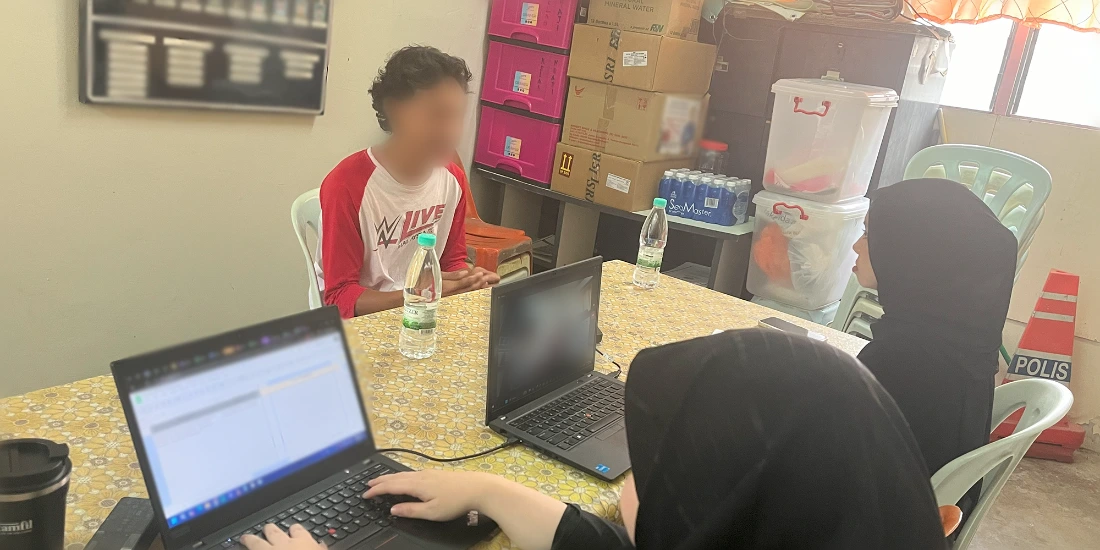

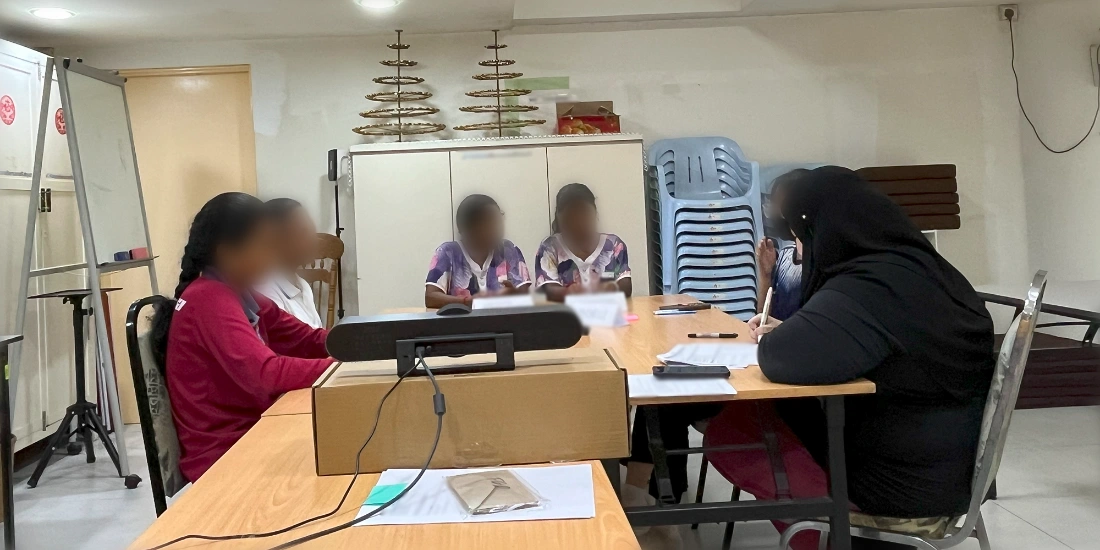

Here’s a glimpse into these sessions, where conversations unfolded in trusted spaces.

Focus group discussion with students in a local temple

One on one interview held in a neighborhood association room

Focus group discussion with housewives held in neighborhood association rooms

Key Takeaways: How to Do It Right

Working with underserved communities isn’t just about changing research methods, it’s about shifting mindsets and rethinking the research operations side from the ground up. Unlike typical UX studies, where participants sign up through online platforms, visit a UX lab and be compensated then and there, our work with Malaysia’s B40 communities demanded a more flexible, relationship-first approach.

Here are some of the lessons that stuck with us, and what others might find helpful if they’re hoping to do more inclusive, community-grounded research:

- Community-Driven Recruitment: Rather than sourcing participants through digital channels or databases, we turned to community leaders and local organizations. These partnerships were essential in reaching people who are often left out of the research conversation.

🔹 Takeaway: If the community doesn’t know you, start with someone they already trust. Local partnerships aren’t just helpful, they’re foundational.

- Relationship First, Research Second: We didn’t jump straight into focus groups and surveys. Instead, we spent time getting to know people through informal chats, meet-and-greets, and simply being present.

🔹 Takeaway: Big words and technical terms can make people feel like they’re not “qualified” to participate. Use plain language. Be patient. And remember: most people don’t think their everyday experience is valuable, until you show them otherwise.

- On-Site Flexibility: A formal research lab wasn’t the right fit for this project. We went where participants felt most at ease: community halls, temples, neighborhood association rooms. We adapted to their schedules too, conducting sessions on evenings and weekends to avoid disrupting their daily lives.

🔹 Takeaway(s):

-

-

- Whether it’s a neighborhood temple or a quiet community center, conducting research in a space that feels safe and known makes all the difference. It helps participants open up and reminds us that the lab doesn’t always have to look like one.

- Housewives, students, and working individuals all juggle full plates. Offering evening or weekend sessions—or just showing you’re willing to work around their schedules—signals that you value their time and insight.

- Planning for the Unexpected: From spotty Wi-Fi to noisy environments, we learned to plan for (and roll with) the unexpected. Our setup had to be portable, reliable, and ready to adjust on the fly without losing focus on the people in front of us.

🔹 Takeaway: Having portable Wi-Fi, alternative recording methods and the ability to adapt on-site means you can stay focused on the person in front of you, not the setup. It also signals professionalism without rigidity.

Conclusion: Human-Centered Research in Action

This research journey went far beyond gathering data. It was about listening, adapting, and building meaningful connections with underserved communities whose voices often go unheard.

This wasn’t just another product design sprint but a shared mission to build a financial literacy platform that could genuinely support Malaysia’s low-income communities.

By embedding empathy into every step of the process, Friendsuretech took meaningful strides toward financial inclusion, supported by our research expertise.

This experience reminded us that conducting UX research with low-income communities requires more than just the right methods: it demands empathy, flexibility, and a commitment to inclusion to design a financial literacy platform that truly resonates with its audience.

In the end, the impact of this research can’t be measured by findings alone. It’s found in the conversations that were had, the trust that was built, and the steps taken toward designing tools that reflect and respect the people they’re meant to serve. We hope this case study contributes to more inclusive research in Malaysia and beyond.

About the Author:

Wai Yee is a UX Researcher with four years of experience driving research initiatives in the fintech and insurance sectors, shaping digital strategies and product experiences. Outside of work, you’ll likely find her chasing hiking trails or perfecting her cup of coffee.